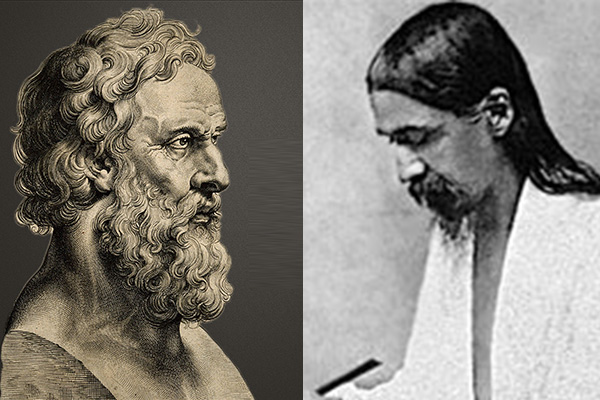

From Plato to Sri Aurobindo

Avant propos

I was born and grew up in Greece, the country of birth, of Socrates, Plato, Pythagoras. I feel privileged for my greek origin, honoured that i learned at school Ancient Greek, the language of my ancestors, being able thus to read the philosophical texts in the original. Grateful to my teachers because they transmitted to me their respect and love for the Ancient Greek language and culture, for the Ancient Greek philosophers. My favouritephilosopher was and still is Plato. Emblematic figure even today, is highly valued by academics as well as by spiritual people around the world.

Plato’s philosophical doctrines

‘No evil happens

to a good man.’

Plato

Plato (427/8 — 347/8 BC) was the son of a wealthy and noble family. He was a philosopher, mathematician, astronomer, writer…

According to Shouler ‘Plato was a polymath at work. He was equally comfortable writing on ethics, epistemology, metaphysics, politics, philosophy and aesthetics (philosophy of art). He made contributions to every branch of philosophy, leaving behind a system of thought that is breathtaking in breadth and depth…

Plato, Socrate’s disc!iple and Aristotle’s teacher, is an inspiring figure among the Ancient Greek philosophers. When his teacher drunk the conium and died Plato was twenty-nine years old. After his teacher’s unjust death he started questioning the democracy of Athens. He was preparing for a career in politics but the execution of his teacher (399 B.C.) had a deep impact on him.

In 387 B.C., twelve years after the execution of Socrates, Plato founded a school in Athens, the “Academy”, for the study of philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, logic, sciences…The Academy in Athens, in Ancient Greece, was the first Institute of higher learning in the Western world. It served until A.D. 529, when it was closed by the emperor Justinian.

Along with teaching in the Academy Plato was also writing books. His dialogues with his teacher, Socrates as a prominent figure, still teach us the concepts of Higher Knowledge, Ethics, Justice, Virtue, Beauty. Socrate’s thought, especially in the beginning of his writings served as inspiration and foundation for Plato’s philosophy. His thirty-five dialogues are generally divided byscholars into three periods : early dialogues, middle dialogues and late dialogues. A few of them are considered transitional works. The early dialogues witness mostly Socrates’ point of view and ideas. Plato, In his ‘Seventh Letter’, described Socrates as “the justest man alive.” His teacher’s unjust death by the court of Athens influenced his later thinking.

Asking himself about the nature of the ideal type of ‘politevma’ he wrote his master piece, the well-known book ‘Republic’ (“Politia’). The ideal State, according to him, should be ruled by a person with adequate knowledge, what Plato would call ‘philosopher-king.’ He points out that ‘The ideal State can never grow into a reality or see the light of day, and there will be no end to the troubles of states, or indeed of humanity itself, till philosophers become kings in this world, or till those we now call kings and rulers really and truly become philosophers.’

The philosopher-ruler or the ‘philosopher-king’ to be able to govern the State should have the right education and posess knowledge of the Good, the vision of the interrelation of all truths to one another. Once this person was ready to govern had to renounce also to all the material posessions.(4) ‘The Republic’ thus is dedicated to the education required of the Philosopher-King.

The ideal state, the norm for a state, according to Plato, is ‘Aristocracy’ (aristos = best + kratos = rule). But not Aristocracy of the blood, but Aristocracy of the spirit. In the ‘Allegory of the Cave’ (Book VII of The Republic) Plato, through Socrates, is talking to Glaucon developing his idea of the qualities of the Philosopher-King: ‘Yes, my friend, I said; and there lies the point. You must contrive for the future rulers a different, a better life than that of a ruler. And then you may have a well-ordered State. For only in the State which offers this, will they rule who are truly rich, not in silver and gold, but in virtue and wisdom, which are the true blessings of life.’

Car Politics and Ethics, according to him, are interconnected. He believes that a State is like a giant person. As justice is the general virtue of the moral person, so also it is justice that characterises the good society.

In the same book, he presents symbolically the predicament in which humanity finds itself. He presents briefly most of his major philosophical concepts. Mainly, that the world revealed by our senses, it’s not the real world. It’s only a poor copy of it. The following selection is taken from the Benjamin Jowett translation (Vintage, 1991), p. 253-5

[Socrates] This entire allegory, dear Glaucon, the prison-house is the world of sight, the light of the fire is the sun, and you will not misapprehend me if you interpret the journey upwards to be the ascent of the soul into the intellectual world according to my poor belief…But, whether true or false, my opinion is that in the world of knowledge the idea of Good appears last of all, and is seen only with an effort. And, when seen, is also inferred to be the universal author of all things beautiful and right, parent of light and of the lord of light in this visible world. And the immediate source of reason and truth in the intellectual. And that this is the power upon which he who would like to act rationally, either in public or private life must have his eye fixed.

[Glaucon] I agree, he said, as far as I am able to understand you.

[Socrates] Moreover, I said, you must not wonder that those who attain to this beatific vision are unwilling to descend to human affairs; for their souls are ever hastening into the upper world where they desire to dwell; which desire of theirs is very natural, if our allegory may be trusted.

[Glaucon] Yes, very natural.

[Socrates] And is there anything surprising in one who passes from divine contemplations to the evil state of man, misbehaving himself in a ridiculous manner; if, while his eyes are blinking and before he has become accustomed to the surrounding darkness, he is compelled to fight in courts of law, or in other places, about the images or the shadows of images of justice, and is endeavouring to meet the conceptions of those who have never yet seen absolute justice?..’

As far as the nature of justice is concerned Plato proposes a way of salvation through a ‘journey upwards’, ‘into the upper world’, through ‘the ascent of the soul into the spiritual world.’

“It’s there”, according to Plato, “that the souls are ever hastening, into the upper world they desire to dwell.”

He thus advocates that the real world can only be apprehended spiritually by the ‘pnevma’ (spirit). He argued thus against the Sophists, who through words and rhetoric they could manipulate their listeners. Words are even more serious sources of illusion, especially in speechmaking and in rhetoric. Someone gifted in word usage, like Sophists, according to him, could pull away people from the truth. Sophists maintained also that the good life is equivalent with pleasure whereas Plato agreed with his teacher’s idea that ‘good life is knowledge and virtue.” In fact, he agreed with Socrates’ view of morality in general and the concept of virtue as function.

Accepting Socrates’ and Pythagoras’ concept of ‘metampsihosis’ (rebirth) he believed deeply in the immortality of the soul.

In the same well-known work ‘The Republic’ Plato criticises the visual and imitative arts. According to him, these arts trade in appearances merely, not in realities. As far as art is concerned, he believed in the art that imitates Ideal realities, not the photographic imitation of that which can be sensed. In his ‘Symposium’ he holds that ‘all beautiful things participate in the Idea of beauty.’

Anselm Froimpach, “Plato’s Symposium”

Sri Aurobindo’s connection with Plato

Sri Aurobindo was a revolutionary, a philosopher, a poet, a visionary. He’s not only a deep explorer of consciousness. He’sthe creator of a new approach, “Integral Yoga”, which inspires today people like Ken Wilber or Andrew Cohen. The story of his life, a deep, enlightened, passionate, mystic adventure inspired most of the spiritual people of our century. His concepts influenced and still have a deep impact on philosophers, psychologists, writers, poets.

Sri Aurobindo was born in Calcutta, in 1872. At the age of seven he left for England. He returned to India in 1893 and he immersed himself in the Indian culture. He became fairly fluent in Bengali, his mother tongue, and learned several modern Indian languages as well as Sanskrit. ‘The more he was immersing himself in the Indian culture the more his admiration was growing. However, it was evident to him that the Indian civilisation could not regain its full stature as long as India was under English occupation. Interestingly, at that time, this was not at all a common view: the Indian elite of those days had widely accepted the superiority of the English culture, and Aurobindo would become the first Indian intellectual who dared proclaim publicly that complete independence from Britain should be the primary aim of Indian political life.’ In 1906 he moved to Calcutta where he soon became one of the most outspoken leaders of the political movement for Indian independence. After 1926 Sri Aurobindo retired entirely to a small, first floor apartment in order to concentrate fully on his inner work. From this time onwards, he left the daily care for the small community that had begun to develop around him, to the Mother, his spiritual companion. This community became the formal beginning of the ‘Sri Aurobindo Ashram’. We know relatively little about what Sri Aurobindo did during the 24 years after his retirement to his appartment. He spoke hardly to anybody, except for a short period just before the Second World War when he needed physical assistance after breaking his leg, and he saw his disciples only 3-4 times a year in a silent “darshan”. During this time he wrote almost five thousand letters to his disciples which were published. He revised as well some of his books like the ‘Essays on the Gita,’ the first two parts of ‘The Synthesis of Yoga’, and ‘The Life Divine’. In His ‘Integral Yoga’ he described the process of ‘the Divine rehabilitation of the ‘Matter’. In the beginning of the XXth century he was writing that ‘man is a being in transition’.

His whole life was a mystic creative experience that brought peace, full concentration on his inner work, deep connection with the Divine Consciousness.

His most important work, is the epic poem, ‘Savitri’. 724 pages, over 24000 lines, beauty of creative expression, poetic visions, it has no equal in the English language. One of the most beautiful spiritual poets of our era.

Sri Aurobindo’s knowledge of the Ancient Greek language allowed him to read Plato’s works like ‘Republic’ or ‘Symposium’ from the original. He was Inspired not only by the philosophy and philosophers but also by the Ancient Greek culture and the lifestyle in general. He points out that ‘The culture and civic life of the Greek city, of which Athens was the supreme achievement, a life in which living itself was an education, where the poorest as well as the richest sat together in the theatre to see and judge the dramas of Sophocles and Euripides and the Athenian trader and shopkeeper took part in the subtle philosophical conversations of Socrates, created for Europe not only its fundamental political types and ideals but practically all its basic forms of intellectual, philosophical, literary and artistic culture.”It’s the Hellenic ideal, according to him, that created the modern mind. With, however, “a greater stress on capacity and utility and a very diminished stress on beauty and refinement.’ Having faith in humanity, he believes that ‘this is only a passing phase. The lost elements are bound to recover their importance as soon as the commercial period of modern progress has been overpassed. And with that recovery, not yet in sight but inevitable, we shall have all the proper elements for the development of man as a mental being.’

Sri Aurobindo is deeply inspired by Plato’s style and profound reasoning. Referring to Plato several times in his writings, hestated that he was inspired by Plato’s ‘subtle reasoning and opulent imagery’.

One of Plato’s main concepts was that each form has its own preconceived idea. When a disciple is asking Sri Aurobindo to clarify that concept, if Plato means by that a creative conception, he replies that ‘Plato had very mathematical ideas about the things. If he meant by it the creative conception then there are several things in it. First of all, it is not a mental idea but what he calls the “Real-Idea’. That is an idea with a Reality and a Power. Now corresponding to every form there is what may be called the archetype, the type-form. It already exists in the Real-Idea before it exists in matter. Everything exists first in consciousness and then in matter.’

When his disciple is asking if Plato’s ‘Real-Idea‘ could be the “Mahar-Brahma’ of which the Gita speaks Sri Aurobindo hesitates to confirm this. He answers that he ignores ‘if Plato had some intimation with the Supramental.‘ He goes on to affirm that ‘as his mind was mathematical he cast it into rigid rational and mental forms.’

In his later writings, however, he will rectify that belief. In ‘Heraclitus’, he points out that ‘even without religion philosophy by itself can give us some kind of light on the spiritual destiny of man, some hope of the infinite, some ideal perfection after which we can strive. Plato, who was influenced by Heraclitus, tried to do this for us. His thought sought after God, tried to seize the ideal, had its hope of a perfect human society.’ A ce propos, i should add that for Plato this perfect human society does not constitute a mere hope or an intellectual abstraction but something tangible, that can be realised, that can be manifested when the level of consciousness of humanity will allow this.

After all, the most important Ancient Greek philosophers, Pythagoras, Socrates and Plato, were, like Sri Aurobindo puts it, ‘seekers of the ‘Apeiron’ (Infinite).

Sri Aurobindo in his later work, entitled ‘The Supramental Manifestation’, goes even further making comparisons between Plato’s concepts and the Ancient Indian scriptures. He states that the Ancient Greek philosophers ‘from Pythagoras to Plato’ were influenced by the Ancient Indian Mystic thought. To ignore the influence of the mystic thought and its methods of self-expression on the intellectual thinking of the Greeks from Pythagoras to Plato is to falsify the historical procession of the human mind. It was enveloped at first in the symbolic, intuitive, esoteric style and discipline of the Mystics, Vedic and Vedantic seers, Orphic secret teachers, Egyptian priests. From that veil it emerged its first aphoristic and cryptic style, its attempt to seize directly upon truth by intellectual vision rather than arrive at it by careful ratiocination. This is the first period of Darshanas in India, of the early intellectual thinkers in Greece. Afterwards came the full tide of philosophic rationalism, Budha or the Budhists and the logical philosophers in India, the Sophists and Socrates, with all their splendid progeny in Greece. The ignorance of the Mystics, our pristine fathers, purve pitarah, is the great defect of the modern account of our thought-evolution.’

A ce propos, Amal Kiran, an Indian scholar and his disciple, in his book entitled ‘Sri Aurobindo and Greece” affirms that a spiritual influence of the Ancient Indian Scriptures on the Ancient Greek philosophy is evident in Sri Aurobindo’s writings. ‘But simply because Sri Aurobindo is Indian by birth, he does not attribute to India all that bears the stamp of spirituality in Greece.’

Plato’s main concept was also that, as in the earthly realm there’s a hierarchy among beings, the same holds true concerning the world of Ideas: ‘The world of sense is the copy of the world of Ideas. In our visible world there is a graduation of beings…The same holds true of the intelligible realm or pattern of the world; the Ideas are joined together by means of other Ideas of a higher order…The Ideas constantly increase in generality and force, until we reach the top, the last, the most powerful Idea or the Good, which comprehends, contains or summarises the entire system.” In a question from a disciple concerning the above statement Sri Aurobindo comments that “Plato was trying to express in a mental way the One containing the multiplicity which is brought out (created) from the One.”

Intuitive knowledge

Sri Aurobindo goes on to affirm that ‘Plato has these ideas not as realisations but as ‘intuitions’ which he expressed in his own mental form.’ In one of his letters to a disciple, published in 1963, in ‘Circle Annual’ he repeats that Plato derives most of his ideas by intuition. Replying to the question whether Plato had derived his concepts of the Good and God the Creator, from Indian books he affirms :”Not from Indian books -something of the philosophy of India got through by means of Pythagoras and others. But i think, Plato got most of these things from intuition.’In his book ‘Letters on Yoga’ Sri Aurobindo one more time refers to Plato as a philosopher with ‘intuition and spiritual development’.

By ‘Intuitions’ Sri Aurobindo means insights, flashes of truth coming from the Higher planes, they are neither mental concepts nor simple knowledge out of experience. This type of knowledge or insight that he attributes to Plato, ‘intuitive knowledge’, distiguishes him from other Ancient Greek philosophers, like Aristotle. Concerning the latter, Sri Aurobindo observes : ‘I always found him exceedingly dry. It is a purely mental philosophy, not like Plato’s.”

He goes on to affirm that the Ancient Indian scriptures, the Upanishads, influenced the ideas of Plato as well as of Pythagoras. According to Sri Aurobindo, ‘The ideas of the Upanishads can be rediscovered in much of the thought of Pythagoras and Plato and form the profoundest part of Neoplatonism and Gnosticism with all their considerable consequences to the philosophical thinking of the West.”

EPILOGUE

They came from different origins, they were living in different countries, their main concepts were named differently. Paradoxically the ideas behind the names were identical : Truth, Virtue, Divine Love and Beauty, Justice, deep love and connection with the Divine Consiousness, Solemnity, Ethical Living…

The East and the West meet and connect harmoniously in their teachings. Sri Aurobindo, updating the Truth for humanity in his era, occasionnally refers to Plato and Pythagoras to connect the East with the Western world. To show that even Plato’s ideas come from the same source, from the Ancient Wisdom.

We hold them dearestly in our hearts for awakening our Consciousness, for enlightening our path, for assisting us to our ascent towards the Divine.

The final paragraph of this article is a quote from the apology of Platos’teacher, Socrates in front of the judges that condemned him to drink the conium. Socrates, fearless and courageous, just and sincere, pure and innocent is trying to prove his innocence, attempting to convince the unconscious judges to apply justice. They declare that he’s guilty accusing him with false accusations. His speech was transmitted to us through Plato in his book “The Apology of Socrates”. ‘For if you think that by killing men you can avoid the accuser censuring your lives, you are mistaken. That is not a way of escape which is either possible or honourable. The easiest and noblest way is not to be crushing others, but to be improving yourselves. This is the prophecy which I utter before my departure, to the judges who have condemned me.’

REFERENCES

1. Plato, ‘The Apology of Socrates’, ‘Πλατων, Απολογια Σωρατους‘, 1991, Kaktos ed., Greece

2. Shouler, ‘in Amal Kiran, ‘Sri Aurobindo and Greece’, 1998, p. 96

3. Plato, ‘Republic’, (Politia), ed. Kedros, 1992, Greece

4. Ibid

5. Plato, ‘The Allegory of the Cave’, Benjamin Jowett translation, Vintage, 1991, p. 253-5

6.ibid

7. Peter Heeh, ‘The lives of Sri Aurobindo’, Columbia University Press, N.Y., 2008

8. Sri Aurobindo, ‘Social and Political Thought’ SABCL, Vol. 15, p. 339

9.Sri Aurobindo, ‘Social and Political Thought, SABCL, Vol. 15’ p. 68-9

10. Ibid, p.69

11. Sri Aurobindo ‘Heraclitus’, 1968, p.12

12. A. B. Purani, ‘Evening Talks with Sri Aurobindo’,, 24/08/1926, p. 496-7

13. Ibid, p. 497

14. Sri Aurobindo ‘Heraclitus’, 1968, p.62

15. Sri Aurobindo, ‘The Supramental Manifestation’, SABCL, Vol. 16, p. 366).

16. Sri Aurobindo, ‘The Supramental Manifestation’, SABCL, Vol 16, p. 338-40

17. Amal Kiran, ‘Sri Aurobindo and Greece’, 1998, p. 96

18. Ibid, p. 96

19. Amal Kiran, ‘Sri Aurobindo and Greece’, 1998, p. 1

20. Ibid, p. 1

21. Amal Kiran, ‘Sri Aurobindo and Greece’, 1998, p. 1

22. Sri Aurobindo, ‘Circle Annual’, 1963, p. 2

23. Sri Aurobindo,. ‘Letters on Yoga’, SABCL, Vol. 22 p. 454

24. Amal Kiran, ‘Sri Aurobindo and Greece’, 1998, p. 96

25. “On Himself’, SABCL, Vol. 26, p. 383

26 Sri Aurobindo, ‘The foundations of Indian Culture”, SABCL, Vol. 14, p. 270

27. Plato, ‘The Apology of Socrates’, ‘Πλατων, Απολογια Σωρατους‘, 1991, Κaktos ed., Greece

No Comments